In March last year, Smithsonian Open Access (OA) arrived online, unlocking copyright-free access to more than three million digital images and items held across the Smithsonian’s museums, archives, libraries, research centers, and zoo. The institution, however, never intended for OA to be a passive repository. Instead, in a pandemic year that saw the collection hit 1.7 million downloads and tirelessly remixed, the Smithsonian has frequently invited creative approaches to OA with the goal of activating its digital holdings.

Hence, Activating Smithsonian Open Access (ASOA), masterminded by the Interaction Lab at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Begun in June 2020, the commissioning program sought proposals from creative technology teams across the world to create immersive and interactive experiences around the institution’s OA collections. Finalists were set to each receive a $10,000 grant, and creative and technical mentorship by the initiative’s partner, Verizon 5G Labs. The output wouldn’t simply be art experiments, but innovative applications that enhance digital interactions with the Smithsonian’s artifacts and broader still, enrich the museum experience.

“As a research and development program focused on visitor experience, it’s critical that the Lab’s work highlights the impact of exploration and investment in museum experience,” Rachel Ginsberg, Director of the Interaction Lab at Cooper Hewitt, tells Jing Culture & Commerce over email. “The question the Lab is asking is: what might happen if we conceive of the museum as a space for meaning-making? To do that requires investment in products, services, programs, and experiences that help people make sense of the objects and ideas on view, beyond the scope of an individual exhibition.”

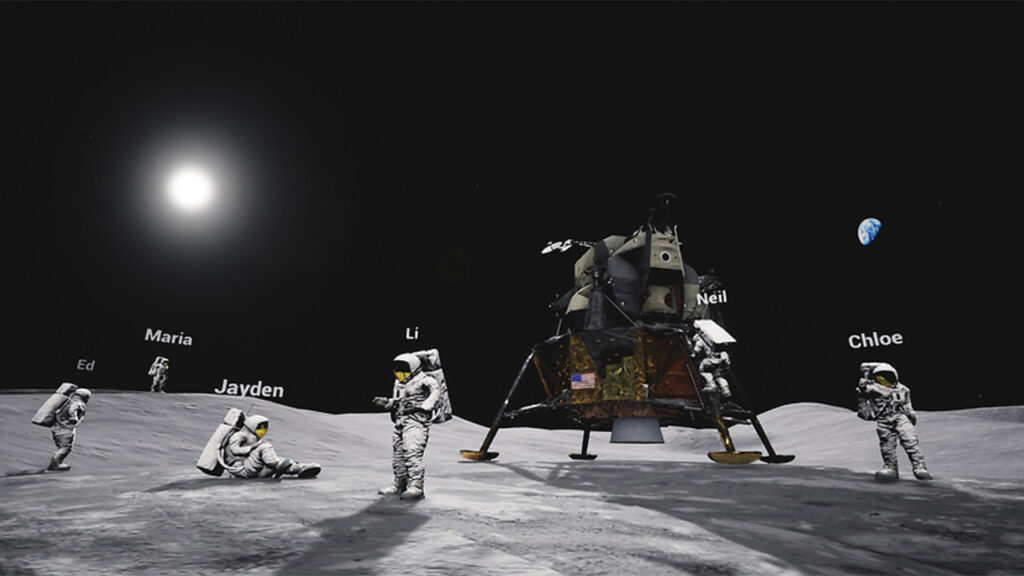

Above: Art Clock (Zander Brimijoin, Daniel Scheibel, Greg Schomburg, Erin Stowell, Lisa Walters and Jiwon Ham); below: ScienceVR Treasure Hunt: Space Mission (Jackie Lee, Ph.D., Yen-Ling Kuo and Caitlin Krause). Images: courtesy of Cooper Hewitt

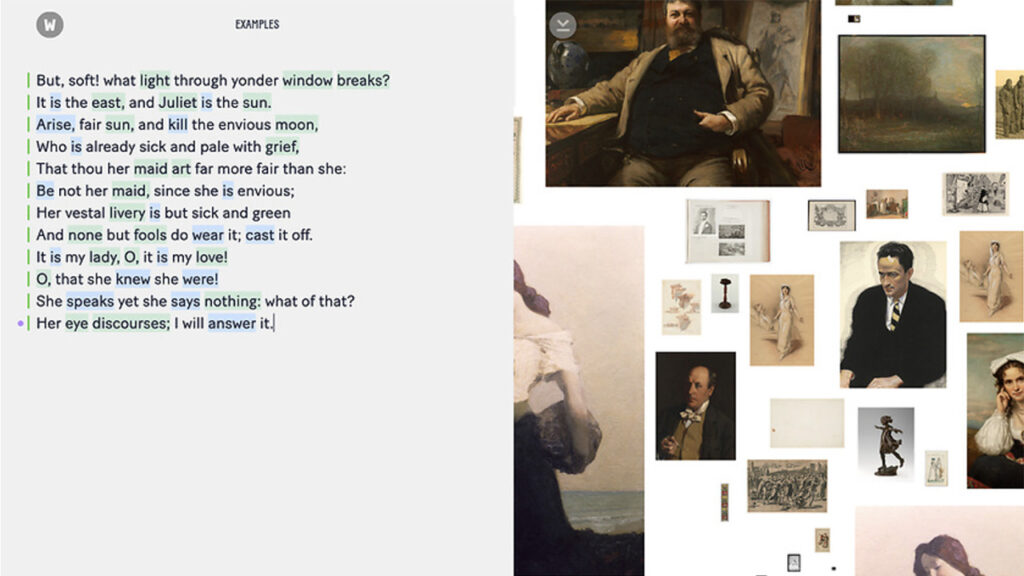

On August 3, the Lab unveiled the first seven prototypes produced as part of ASOA. There’s the Art Clock, which displays analog time using the angles and lines within images as hour and minute hands; Writing With Open Access, a tool that calls up images based on a user’s textual input; and ArtEcho, a virtual reality experience built around the acoustic properties of 3D objects.

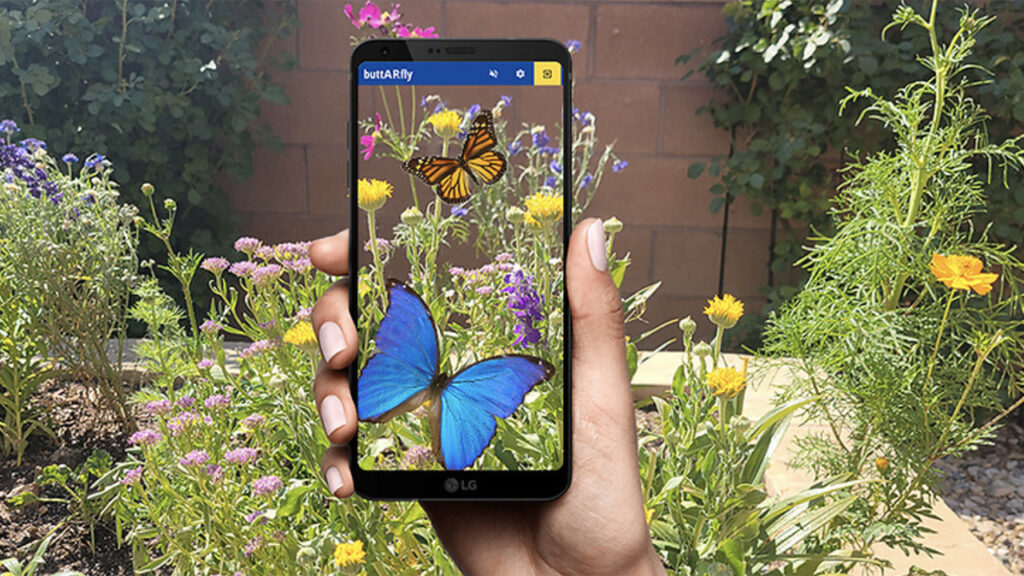

A clutch of augmented reality platforms — ButtARfly, Casting Memories, and Doorways into Open Access — center personal interactions with living and historical artifacts, respectively butterflies, the Benin Bronzes, and the environments of the Belle Époque. Finally, Treasure Hunt: Space Mission, an interactive social learning game, allows young players to track down and collect OA items in a virtual setting. The public can engage with all projects online and provide feedback on their experiences.

Writing with Open Access (Jono Brandel, Sunny Oh, Hiroaki Yamane). Image: courtesy of Cooper Hewitt

Ginsberg is rightly thrilled about the first batch of ASOA projects, arraying as they do the diverse and playful ways technology can vivify a museum’s catalog. “The most exciting part, without question, is the range of projects that all came out of this one program,” she says. Below, she goes on to detail the impetus behind ASOA, technology’s increasing role in museum presentations, and just what goes into a well-designed visitor experience.

What was the thinking behind launching ASOA?

The Interaction Lab has been committed to building a creative commissioning program since its inception. We recognized early on that we had an opportunity to engage the wider design community in thinking and experimenting with us, so why not invest in that potential?

Does the Lab plan to further support or develop these projects for real-life museum applications?

We’re in the process of exploring this now, but have already identified a few different pathways. We started by involving our Smithsonian colleagues in the program as mentors and judges to ensure we were setting it up for success inside the institution. Now that the prototypes have arrived at launch, we are starting to convene conversations within the Smithsonian to raise awareness about the ASOA program and the prototypes generated from it. We’re also making plans to connect each team with groups inside the Smithsonian who might be interested in taking these projects forward.

In addition to the public program launch, we also plan to do an internal presentation about ASOA for Smithsonian staff that goes into detail about what we did, how we did it, and the individual projects each team made. That way, we’re modeling outcomes as well as sharing what we’ve learned about creative commissioning as an approach.

Above: Casting Memories by Loot Merch (Mayowa Tomori, Michael Runge, Rita Troyer, Olivia Cueva, and Olu Gbadebo); below: ButtARfly (Jonathan Lee, Miriam Langer, Rianne Trujillo and Lauren Addario). Images: courtesy of Cooper Hewitt

The Interaction Lab’s stated mission is to reimagine the “Cooper Hewitt visitor experience.” What does this experience look or feel like to you?

The most important thing for visitors to take away are the connections they made between things they already knew with new ideas from their museum visit. Museum experiences themselves should be widely varied, within a single museum visit and among a range of museums depending on their content and focus. The key driver of a well-designed museum is that it is designed to be experienced. That means not thinking about the objects first, or even the stories and content first, but about people first.

What are your thoughts on how digital and technology have become increasingly central in museum exhibitions and experiences?

I think technology being a central part of the museum experience makes sense as it becomes a central part of the human experience. That said, we need to have good reasons for making the choices we do about when and why to deploy it. In my view, tech works in museums when it’s being used to offer some kind of utility that might not be otherwise available — offers design flexibility without sacrificing inclusion, helps to deepen understanding and engagement.

The other really exciting area where technology has been working during the pandemic and can keep working is bringing remote audiences to museum programs. We, like many other museums I know of who moved to online programming, have experienced an incredible surge in participation from faraway audiences we had never had access to before. Not only are we excited to keep interacting with those audiences, but we are actively looking to explore hybrid programming that would bring remote audiences and in-person audiences together, and offer an equitable and exciting experience to all involved.

For you, what are some key considerations designers of such tech or digital-centered museum interactions should take into account as they plan such projects?

The first and most important question any designer or technologist should ask, in museums and outside, is “Why?” Why am I doing this? Why am I using technology in general, and what reasons do I have for choosing one specific technology instead of another? Is the proposed technology adding to the experience, or is it expected to be the experience? If one can’t answer these questions clearly and with purposeful strategic alignment, it’s not yet time to build, and may never be.