In June this year, two Egyptian Book of the Dead fragments were digitally reunited.

These funeral spells, which ancient Egyptians wrote on their deceased’s possessions like mummy wrappings, coffins, and figurines, were intended to serve as instructions for the dead in the afterlife. Today, surviving manuscripts or fragments, forming less a book and more a loose collection, are scattered in museums across the world — from the British Museum to the Metropolitan Museum of Art — with the largest Book of the Dead collection in North America being held in the J. Paul Getty Museum, which houses seven papyri and 12 linen mummy wrappings.

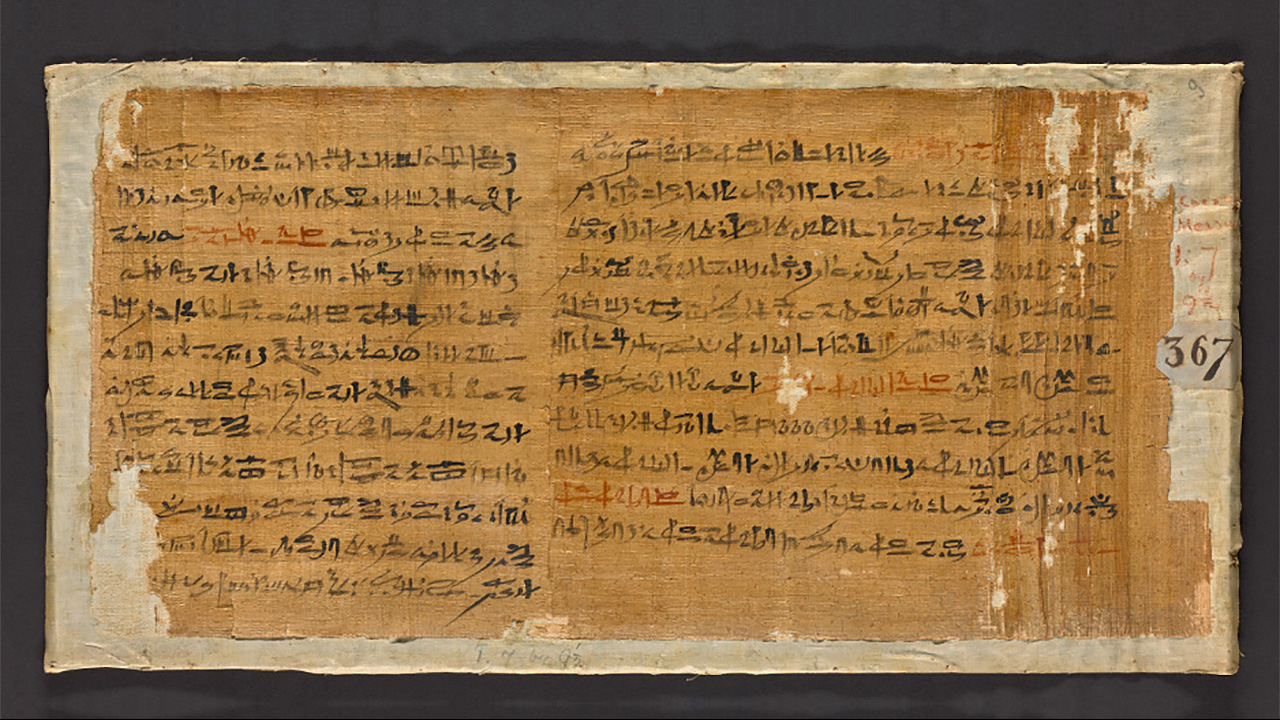

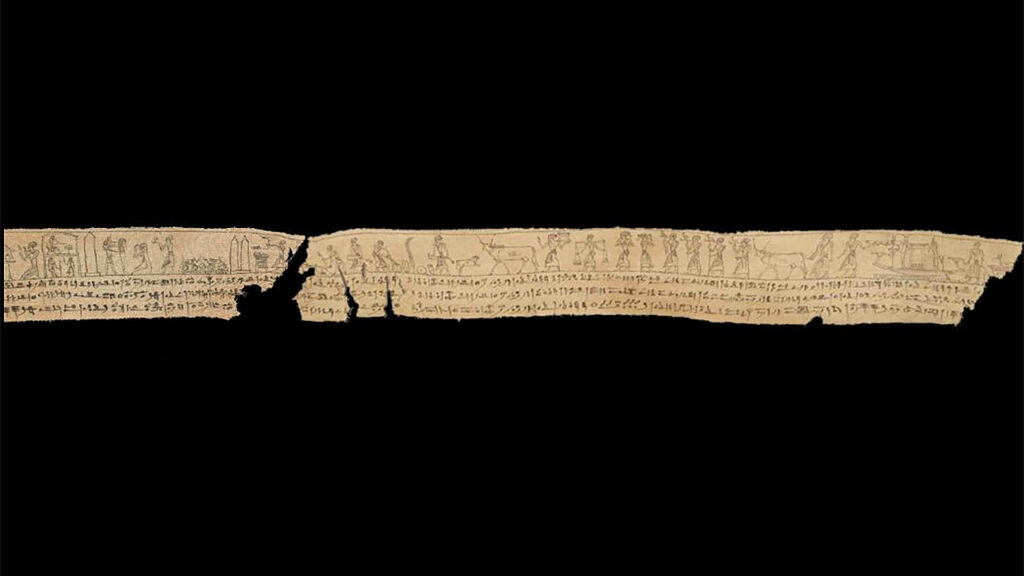

It’s at the Getty that Judith Barr, a curatorial assistant in the Getty Villa’s Antiquities Department, managed to piece together a 2,300-year old mummy bandage, once used to wrap Petrosiris, a high priest of Thoth. She conjoined a segment from the Getty Museum’s collection with another located half a world away, within the archives of the Teece Museum of Classical Antiquities at the University of Canterbury (UC) in New Zealand. Teece’s fragment was located by Getty curators in UC’s digital catalog, facilitating a virtual match.

The newly reunited Book of the Dead spell, pieced together by a fragment from UC’s Logie Collection, held at the Teece Museum of Antiquities (right) and another from the Getty Museum (left). Image: University of Canterbury

“There is a small gap between the two fragments; however, the scene makes sense, the incantation makes sense, and the text makes it spot on,” Alison Griffith, Associate Professor at UC’s Classics department said in a statement. “It is just amazing to piece fragments together remotely.”

The discovery hasn’t just enabled Barr and her colleagues to array and translate an entire funerary spell, but contributes in no small way to the study of Egyptology. It also highlights the importance of digital archives, in making collections accessible to the public and professionals to spur academic study, research, and exchange. Barr and Sara Cole, Assistant Curator in the Getty Museum’s Antiquities Department, tell Jing Culture & Commerce that Getty’s latest Book of the Dead reassembly will inform an upcoming catalog and below, share more about the museum’s ongoing digitizing efforts.

Could you fill us in on the Getty’s Book of the Dead collection and how it’s being digitized?

Cole: The Getty has a group of 19 manuscripts that contain ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead spells. These texts entered our collection in the ’80s, but they’ve never been displayed to the public or properly studied, translated, and published as a group. To make our collections as accessible as possible, we’ve partnered with Foy Scalf, an Egyptologist at the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, who’s currently studying and translating these 19 manuscripts so they can be comprehensively published in a digital open access publication.

We examined [the 19 manuscripts] in person and then had new photography taken, which is now available on the collections pages. That photography will be used in the digital publication. One of the benefits of the digital publication is readers will be able to zoom in and see these inscriptions and the illustrated vignettes in tremendous detail that wouldn’t be possible in a physical publication.

Launched in 2013, Getty’s Open Content Program is a digital archive of more than 10,000 images — including (clockwise from left) an 18th century lantern design, Max Hutzel’s 1960s photograph of a sculpture in Santa Maria church, Sellano, Italy, and a 1694-1698 print by artist Antoine Trouvain — that are free to use. Image: Getty’s Open Content Program

How else is the Getty enhancing its digital archives?

Barr: My work in curatorial over the last six-and-a-half years has been part of a project that’s designed to increase the amount of information on our collection pages, so that they act as a kind of online scholarly catalog. We’ve made bibliography available, provenance descriptions, all kinds of information, and that’s essentially serving as a digital archive of the museum’s collections. We’re building out information on our collection pages, so every single object in our collection has a collection page. We have 46,000 records in the antiquities collection — everything from coins to individual fragments. And that’s part of what helps make it discoverable.

Cole: In conjunction, there’s also a number of wonderful open access publications that are being published on our collection using Quire, which is an open access framework developed by Getty Publications. We are currently getting the tens of thousands of objects in our collection photographed, so there can be images available with their records on the collection pages.

We’re in a constant process of reviewing and revising object descriptions that appear online so that we have up-to-date accurate information for people to access. We’re really making an effort to potentially publish our own collection, and have done a series so far of open access digital volumes, with in-depth discussions of groups of objects in our collection. Our group of 19 Book of the Dead manuscripts is part of a current project, where we will be publishing these through Quire as one of these open access digital publications.

The digitization process at the Getty Research Institute. Image: J. Paul Getty Trust

What do you think is the primary benefit of having technology involved in museums’ conservation, archival, and curatorial efforts?

Cole: [Technology] does have value in so many different ways. In terms of furthering scholarly research, it helps us bridge gaps and have a broader understanding of pieces in our own collection — how they relate to other pieces from similar places or time periods or in terms of provenance — and to understand objects that all came from the same collector or at some point were owned by the same individuals. But in terms of making the collection accessible to the public, the more information we make available online the better we can enhance their appreciation and understanding of our collections.

Barr: Looking outside of our collection, that’s always going to be a very personal choice as to what you need to prioritize for your own individual collection. Some collections can’t be digitized and digitization is maybe not appropriate for specific objects, but maybe there’s technology that would be helpful in supporting those objects and their caretakers.

We’re so fortunate to have the resources to be able to work with our photography team, outside scholars, our database engineer — there’s dozens of people helping make these objects and these records available. Our projects and databases like the Book of the Dead will hopefully provide a platform to connect those collections that don’t necessarily have the resources to mount full digitization or full provenance information about their objects, but we can connect them here in this digital space.