The first emperor of China was a profoundly superstitious individual. Not content with mortal supremacy, Qin Shi Huang commanded 700,000 workers to create an army to defend him against evil in the afterlife — more than 2,000 years later, China’s office workers can ward off daily tedium by ordering limited-edition terracotta miniatures sold on Taobao. Only the speediest online shoppers that is, it may have taken 40 years to build the emperor’s army of clay warriors, but their modern counterparts sold out in minutes.

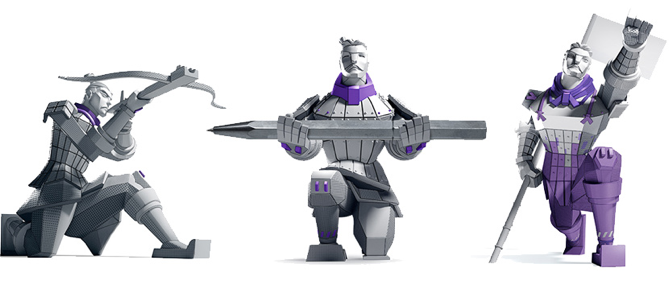

Within days, the figurines were reselling for more than 20 times their original value on Taobao and yet, the frenzy surrounding the 10-cm plastic models, available in three striking poses and suitable for holding small objects, was entirely unsurprising. Not only did Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum release a mere 600 models, but wenchuang, museum products inspired by China’s rich cultural history, are all the rage with China’s young and increasingly culturally-driven online shoppers.

As Zhang Jintao, director of culture and industry at Xi’an museum, explained to Beijing Youth Daily, “We’re always working hard to think of ways to keep people engaged after they have visited cultural relics, how to keep people pondering, how to ensure people continue to feel the charm of traditional culture.”

Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum’s playful reimagining of the Terracotta Army were snapped by online shopping in under an hour. From the Taobao shop “兵马俑淘宝”.

Indeed, from Ming dynasty inspired Forbidden City makeup sets to Sichuan Opera’s set of colorful facial masks, China’s museums are reimagining and reinvigorating what it means to be a purveyor of culture in an age of e-commerce. The wenchuang trend was given impetus by The Ministry of Culture’s 2016 initiative to “strengthen guidance and support the development of cultural and creative products in local cultural and cultural units,” but can equally be explained by access to cheap manufacturing that exists in China and newfound domestic pride in China’s rich cultural history.

And it’s not just Chinese museums monetizing their IP by selling quirky collectables and branded everyday products — The Palace Museum made 1.5 billion yuan (roughly $216 million) in 2017 — western cultural institutions are getting in on the act too. The British Museum’s Tmall shop has enjoyed spectacular success since its 2018 launch, The V&A collaborated with Chou Sang Sang to create a jewelry line, and the MET will launch a range of products in the coming year through its partnership with product licensing experts Alfilo Brands.

The message is clear, cultural institutions hoping to broaden brand awareness in China need to meet consumers where they are, namely on Taobao. A millennial living in a third-tier Chinese city may have never visited London, but they’re still interested in vacuuming the apartment with a British Museum-themed vacuum sealer bag.

But success in the booming wenchuang market isn’t as simple as picking an item and slapping a museum label on it. The days of posters and keychains are over. Products must be practical, playful, and well made. The promotional words and images used to announce the model Terracotta Warriors embodied this spirit with one caption accompanying an image of a model warrior reading, “love needs courage, no matter if it’s memo pads, a mobile phone or tissues, I will help you carry it.”

According to Du Minghui, the pioneer of the museum’s product campaign, the models were the result of intensive research and planning that started with the question “How do young people think about the terracotta warriors? We checked many websites to see what content appears when searching ‘Terracotta Warriors’, we discovered many netizens believe Qin Shi Huang was a model collecting hobbyist and the Terracotta Warriors are simply a large-scale order of models by Qin Shi Huang. From this we got the idea to manufacture Terracotta Warrior models.”

Following the inspiration, researchers at the museum dug deep to further develop a suitable product. “We spent around a month delving through history books and pictures,” says Du. “We studied the different types of terracotta warriors and horses with the hope allowing ourselves to be fully creative while staying true to the original form.”

The 8,000 terracotta warriors might be a priceless wonder of the ancient world handed down to posterity, but for the Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum products in their image have a very real price, and as Du acknowledges “The models have been so popular, we will release similar wenchuang products to meet the needs of everyone.”