The woman appears like a vision from a surreal, high-end fashion shoot. Powerful beams of sunlight pass across her body as she strolls along the bottom of a swimming pool. Above her, aquamarine waters ripples — only, she is fully-dressed and thoroughly dry. This playful optical illusion is the installation “Swimming Pool” by Leandro Erlich, and it has taken Beijing’s urban cool by storm this summer, causing long lines and clogging up social media feeds.

Cici is one such youngster. She spent an hour waiting in line to access the exhibition, which takes up all four floors of the Central Academy of Fine Arts Art Museum (CAFAM) as well as its outdoor spaces. Having seen Erlich’s work at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, Japan, the Beijing-native was keen on seizing her chance closer to home. “The CAFAM exhibition is a perfect opportunity, and it was a wonderful experience to ramble at the bottom of a swimming pool,” she said.

The work is part of Erlich’s show The Confines of the Great Void, and aside from standing as the Argentine artist’s most extensive solo exhibition to date, it’s also being cited as evidence of a continuing shift in Chinese art away from intellectualized exhibitions and toward social media validity. The latter is a concept one Weibo user succinctly captured, writing that “the experience is more like watching the crowd, rather than seeing the artwork.”

In the latest version of “Batiment,” Erlich takes inspirations from the classical shop fronts in Chinatown. Photo: Courtesy of the Central Academy of Fine Arts Art Museum.

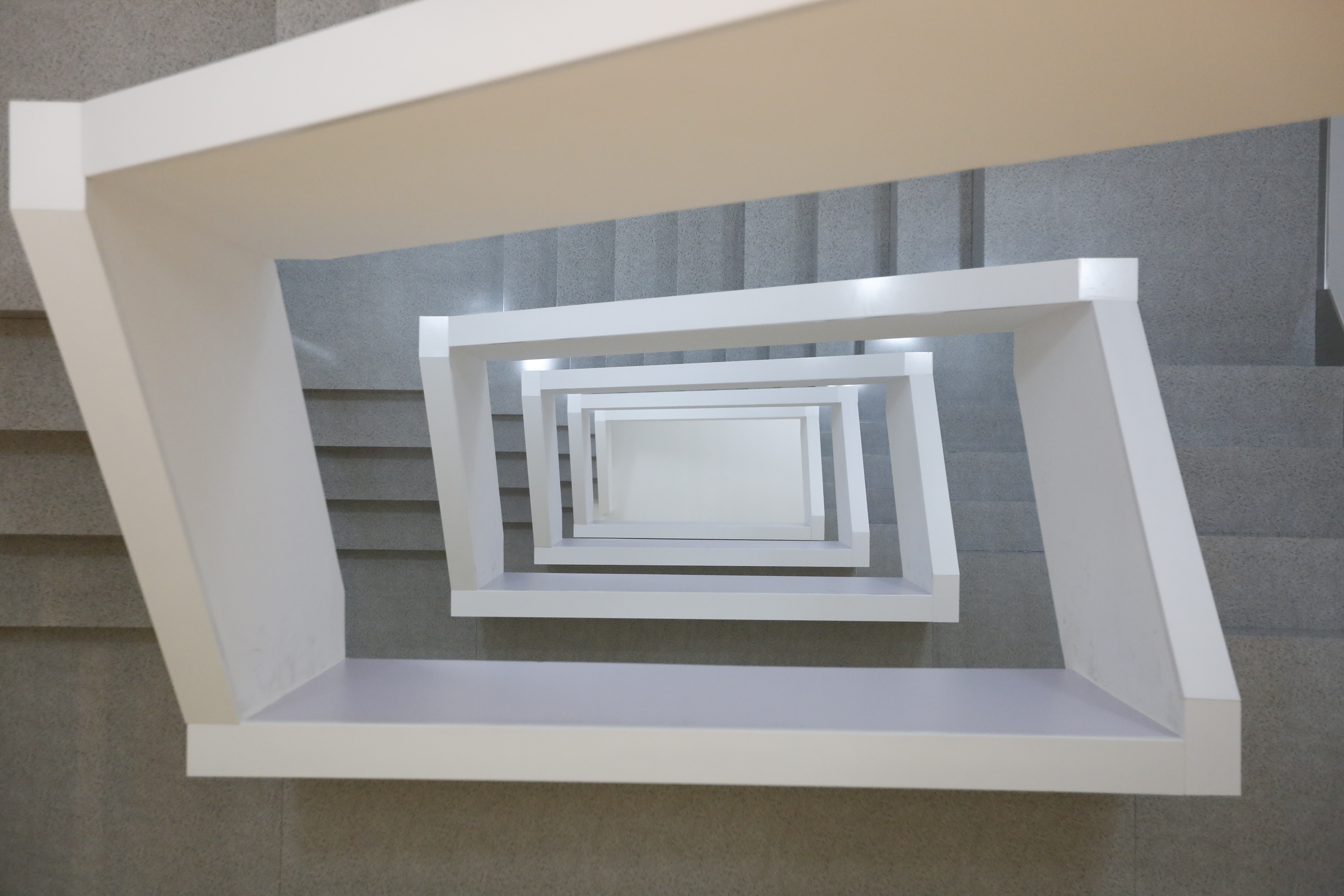

From “Staircase,” which places the viewer at the top of seven-story stairwell turned on its side, to “Batiment,” which flattens a large-scale model of a typical building front with the use of a huge mirror, the engaging and photographic nature of Erlich’s work makes it easy to understand why it’s exploding online (the exhibition’s hashtag on Weibo, for example, has been seen nearly 7 million times.)

The “Staircase” refers to the design of staircases in CAFAM’s building, which challenges people’s common sense. Photo: Courtesy of the Central Academy of Fine Arts Art Museum.

Approached a different way, the buzz surrounding CAFAM’s newest offering is simply another indication of the burgeoning demand for high-quality art — both Western and domestic — in the Chinese capital. Other examples include the 150,000 Chinese who flocked to the UCCA in July for the country’s largest ever Picasso exhibition and Xu Bing’s recent show at the Today Art Museum, which sold out in record time.

But a central charge levied at The Confines of the Great Void is that it’s a wanghong exhibition: a name given to increasingly popular artistic ‘spectacles’ that lack critical engagement and are designed primarily with social media aesthetics in mind. Paul Smith’s Pink Wall exhibition, which toured Shanghai, Beijing, and Shenzhen in 2018, and CHANEL’s Mademoiselle Privé exhibition from earlier this year stand as examples of brands that have plugged into this trend, followed by great commercial success.

CAFA’s status as one of China’s most prestigious art institutions, one which claims esteemed artists like Xu Beihong and Xu Bing as alumni, is the background for the exhibition’s criticism. Simply put, residents feel it shouldn’t dabble in something as lowbrow as wanghong exhibitions. CAFA’s detractors also point to the museum’s recent commercial activity, which includes its role in a series of exhibitions called Invite You to Visit, a campaign that was led by the Chinese smartphone brand OPPO to promote the practice of posting gallery artwork on Weibo.

CAFAM’s director, Zhang Zikang, rejects the negative accusations being lobbed at the museum, saying that “wanghong indicates the popularity of the exhibition, but it does not mean a weakening of academic values. We do not reject potential business opportunities that popularity can bring us.”

To this point, Phil Tinari, the director of the UCCA, recently stressed the importance of contemporary Chinese museums remaining in touch with their young, urban visitors across digital platforms noting that “now, so much of our outreach is centered on collaborations with new marketing channels, social media platforms, and opinion leaders.” And Erlich’s exhibition comes at a time when interactive, immersive, and experiential art exhibitions have become hugely attractive to younger demographics. From 2016’s Rain Room at the Yuz Museum to teamLab’s most recent presentation at TANK Shanghai this year, Chinese art lovers are swarming to exhibitions featuring experimental artwork.

But this Chinese art consumption remains in its early stages, and the growing popularity of museums is only now starting to push against the idea of art as a culturally elite activity. Even if much of the popularity around Erlich’s work is superficial, engagement with the arts — however it occurs — is a good thing in itself and creates a building block for future conversations.

Contemporary artist and CAFA professor Qiu Zhijie, known for his conceptual ink maps, agrees and took this position in a recent panel on the curatorial strategies of exhibitions. “The conversation about interaction [between viewer and artwork] is being overstressed,” he said, and ultimately, Qiu believes that the role of an exhibition is to encourage personalized experiences and independent thinking.

Accusations of China’s art scene being overly commercialized are nothing new. Beijing’s 798 Art Zone and Caochangdi, an arts district in the north-eastern part of the city, have been increasingly focused on commerce and retail concerns. E-commerce shopping is also playing a part in the monetizing of museums and galleries, with Tmall having already initiated collaborations with 24 museums to produce highly-popular wenchuang (culturally-inspired products created by museums).

The marketing and curatorial strategies of CAFAM may be a sign that the line between culturally significant contemporary art and commercial art is blurring. In some ways, this is not a bad thing, and Erlich’s exhibition offers a promising start in museums’ quest to engage ever-larger audiences and attract those viewers coming from outside the arts community.

Visitors may have complained about the crowded and noisy experience of moving through CAFAM’s most recent exhibition, and although establishing healthy and sustainable connections with museum-goers is important, Chinese museums increasing exposure and capitalizing on cultural consumption may just be the new status quo.