By the time the curvaceous white domes of Zaha Hadid’s Galaxy SOHO were unveiled in 2012, starchitects had been descending on the Chinese capital for years. Rem Koolhaas’ radical “anti-skyscraper” housing China’s state broadcaster was already iconic, the giant steel egg Paul Andreu conceived for National Centre for the Performing Arts had been welcoming audiences since 2007, and the Beijing Olympics had tasked the globe’s most prestigious firms to design its stadia.

Nearly a decade on from her debut Beijing building, however, Hadid has eclipsed the rest, comfortably emerging as China’s most popular foreign architect. A trio of SOHO projects followed: cultural centers in Nanjing and Changsha were commissioned, and, posthumously, Beijing’s Daxing Airport and the Shenzhen headquarters of consumer electronics giant Oppo built.

Today, few Chinese metropolises are without a Zaha Hadid, an affinity that was certainly mutual. Hadid traveled by train through China in the 1980s and was entranced, enamored not only by those she met, but the similarities she found with her native Iraq, in particular the way China’s waterways shaped cities, sculpted landscapes. Fitting then that the first China exhibition devoted to Zaha Hadid Architects takes place at Modern Art Museum Shanghai (MAM), which stands on the banks of the Huangpu River, perhaps China’s best-known waterfront.

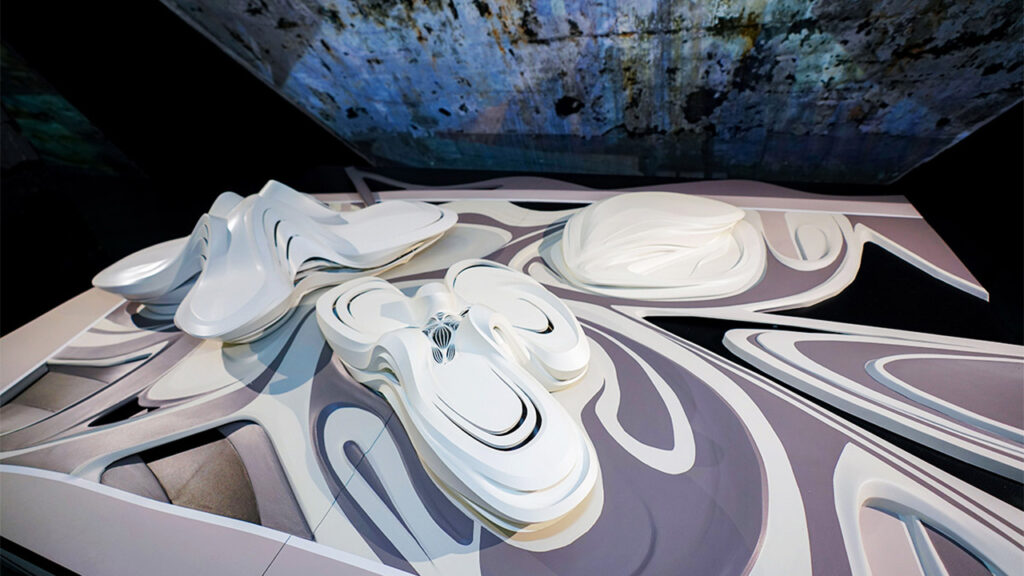

The exhibition spans four decades’ worth of ZHA projects such as the Oppo headquarters in Shenzhen (above) and the Changsha Meixihu International Culture & Arts Centre (below). Images: ZHA

ZHA Close Up – Work & Research is a sweeping retrospective of projects stretching from 1982 to the present. It’s a show that unpacks logic and meticulous planning, one that details how the studio has imagined, rendered, and constructed its wonders. It also spotlights projects from Zaha Hadid Design through which the first woman to receive the Pritzker Prize presented equal flair to furniture and fashion.

Here, Shai Baitel, MAM Shanghai’s first artistic director, discusses the exhibition with Jing Culture & Commerce.

How would you explain the popularity of Zaha Hadid Architects in China?

Although her first structures were built in the West, Zaha was regularly present in Asia from early on in her career. Her 1982-1983 Hong Kong Peak project, for example, was the pivotal work that propelled her name into international renown. As her designs evolved, Hadid became an international sensation because her buildings are themselves works of art. This philosophy continues to have great resonance in China.

As population growth in China has led to vast development projects over the past several decades, various cities have engaged with international and local architects to boldly define urban space, and Zaha Hadid has been one of the preferred names for some of the country’s most significant projects.

Could you share the backstory to the exhibition? How did it come into fruition?

I first met Zaha Hadid in 2015 when we were starting talks on discussing the possibility of building a ZHA permanent museum. She had recently bought property in Miami, and wanted to spend more time there, and I thought it would also make an excellent location for the museum. Our last meeting happened in March 2016 in the Mercer Hotel in New York. Zaha was unwell, but insisted we still meet. But the encounter immediately felt different. Zaha was breathing very heavily, but told me it was nothing, and that she was going to Florida to rest. Four days later, she passed away.

By the time I met Patrik Schumacher, ZHA’s principal, and later Manon Janssens and Woody Yao, who are heading the archive and design departments respectively, I was thinking about Zaha’s legacy and how remarkable her approach to life and design was. And I knew I wanted to give her the honor she deserves with a distinctive museum exhibition and experience.

Also spotlit in the exhibition is Hadid’s art and design practice, including her products for Zaha Hadid Design and the ZHD Collection. Image: ZHA

Could you detail the presence of Zaha Hadid Design and the ZHD Collection at the exhibition?

Zaha’s original approach to art and design was not focused solely on architecture. From her early university projects, she blurred the lines between fine art, design, and architecture. As she rose to fame, brand and product designers reached out to her asking for ways to incorporate her idiosyncratic vision into their work. In these collaborations —with Melissa Shoes, Alessi, among others— Zaha embedded her DNA into the products, several examples of which we are presenting in our exhibition.

Some of the works come from Zaha Hadid Design, formed in 2006 out of a need to create a distinct platform for Hadid’s distinct dialogue of contemporary design. Today, it is defined by Hadid’s inventive methodology and signature design in furniture, lighting, and fashion. Additionally, the ZHD Collection, founded in 2014, further expresses Hadid’s vision in an uncompromising pursuit of excellence and non-conformity to define the acclaimed brand and ensure its timeless presence within the design world.

What can visitors to the exhibition expect? What do you hope they take away?

I very much hope visitors to MAM Shanghai can understand the life, work, and philosophy of such an avant-garde thinker, architect, designer, and artist. I want visitors to understand the risks she took, and how uncompromising she was in following her inner voice. I want the audience to realize how exceptional it was for an Iraqi woman to have such a profound influence on the discipline of architecture and I want visitors to leave wanting to learn more, and come back to see the exhibition again, bringing along their family and friends.