Over the past few years, the conversation surrounding cultural restitution has increased in volume — in both measure and urgency. And yet, despite the growing amount of scholarship and activism swirling the cause, Open Restitution Africa (ORA) has found, “African scholars are the least cited,” even as the continent’s material heritage has been blatantly looted and dispersed across Western institutions. It’s the kind of data point that throws the repatriation space into stark relief.

So yes, while the recent wave of returns by museums has been heartening (and overdue), it’s but the germ of a process that should be ongoing, active, and open. It’s why, to urge it along, Chao Tayiana, Founder of African Digital Heritage, and Molemo Moiloa, Head of Research at creative consultancy Andani.Africa, have masterminded ORA. Begun in 2020, the project is aggregating and making available data on the restitution status of African artifacts, in a bid to advance transparency around the repatriation process.

“We have three main pillars of what we’re trying to do: to make restitution data transparent, accessible, and centralized,” Tayiana tells Jing Culture & Commerce. “The restitution process in itself involves several actors, nations, and a lot of complex data. So what happens when you collate this data and put it in a format and a place where you can see it’s not just a country, but across the continent as a whole?”

“We have three main pillars of what we’re trying to do: to make restitution data transparent, accessible, and centralized,” says Chao Tayiana, Co-Founder of Open Restitution Africa. Image: Open Restitution Africa

The initiative is currently in its discovery phase, during which the team is assessing the information to be captured in order to map out an initial framework based on open data. In addition to its own research, ORA intends to ask museums on the African continent to submit their own data about the number of objects that have been returned and the number still under request. “Museums are key participants in the process,” emphasizes Tayiana.

Once launched in 2023, ORA will serve as a one-stop information portal, not just for cultural practitioners, but for the most vital of stakeholders: the African public. Cultural repatriation, after all, is more than just a bureaucratic or legal concern. “It is a public discussion,” says Tayiana. “The citizens and communities that have been disenfranchised from the cultural material have a right to know what is going on.” A pre-launch series of podcasts and webinars by ORA aims to further add to that understanding.

Indeed: whether a Benin Bronze or a Balot sculpture, these artifacts hold for their country and culture of origin weight beyond the aesthetic. They’re power objects that speak “about nationhood, about cultural identity, about determination of history,” notes Tayiana. Which is what also drives ORA’s centering of African perspectives — from the point of access to the audience doing the accessing.

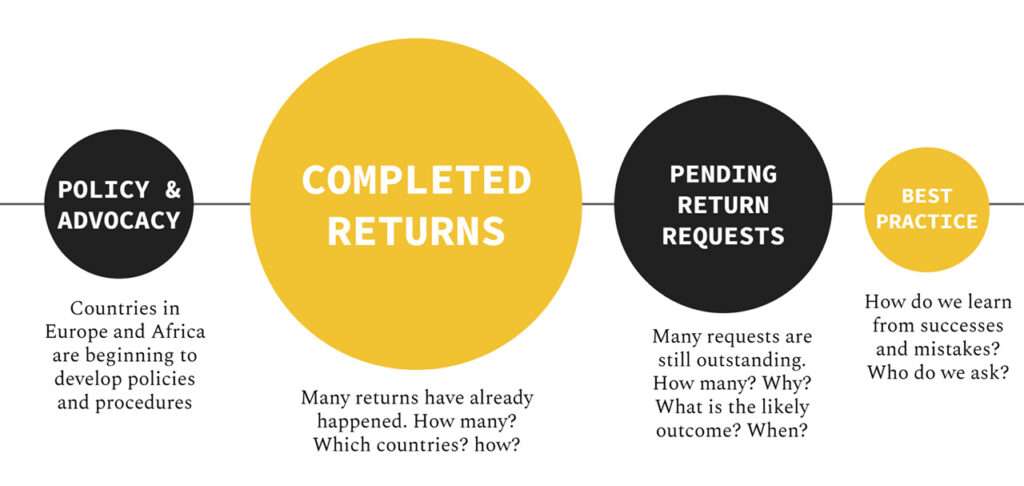

The project aims to collate a complex web of data from return policies to restitution requests to actual returns. Image: Open Restitution Africa

Such access has of course been made possible with the advances in digital technology, which has increasingly surfaced in discussions surrounding cultural restitution. Most pointedly, digital repatriation, wherein objects are “returned” to their country of origin in digital form, has long been mooted by institutions as a form of resolution.

It’s a practice that, with its ethical gaps (digitizing a looted object, for one), remains limited in impact. Quite simply, as Ghanian academic Dr. Kwame Opoku wrote in 2015, “Could anyone propose to the Egyptians to accept a virtual image of Nefertiti whilst the original bust of the African queen remains in the Neue Museum? Would the Chinese be satisfied with virtual images of the precious treasures looted by the French and the British troops from the Summer Palace?”

Or in Tayiana’s words, “Digital data is not a substitute for having items physically returned.” And to be clear, ORA’s mission is pointed firmly toward using technology to motivate the repatriation discourse and action by encouraging accountability and empowering stakeholders with information. “We have this opportunity to use [digital] as a moment of restoration where we can reset the terms of the kinds of data we’re looking for,” as Moiloa put it in 2021.

As part of that restorative process, the hope, Tayiana adds, is for ORA’s visitors to use its data to develop insights and make informed decisions: “A key measure of impact is how people can take the data and reuse it.” That access, however, is only the beginning. Once the legal and bureaucratic complexities are teased out, aggregated, and grasped, what’s left is the central imperative that is restitution. And that — “an issue of justice, human rights, and morals,” as she puts it — remains plain enough, with or without data.