The demand for NFTs isn’t so small that it hasn’t taken India by storm. Over 2021, the country has become home to a growing coterie of digital creators and multiplying NFT marketplaces from BeyondLife.club to Bollycoin to WazirX, the latter established by India’s largest cryptocurrency exchange. Bollywood celebrity Amitabh Bachchan has launched a record-smashing NFT collection, while the Hindustan Times has tokenized some of its historic coverage. The sector is buzzing enough that earlier this month, India’s 2022 Union Budget made news for introducing a 30 percent tax on the rather nebulous class of “virtual digital assets.”

Nor is Indrajit Chatterjee, Founder of Mumbai gallery and auction house Prinseps, immune to the market’s promise. “I do see a huge and vibrant NFT market in India within a couple of years surely,” he tells Jing Culture & Commerce. He should know from experience: Prinseps, after all, masterminded India’s first NFT art auction. Initiated on January 14, the sale featured 35 NFTs of Gobardhan Ash’s rare works on paper — figurative, earth-washed images the pioneering artist produced between 1948 and 1951, serving as a spark for Indian modernism — which buyers could purchase as the original physical works, as 1/1 NFTs, or both.

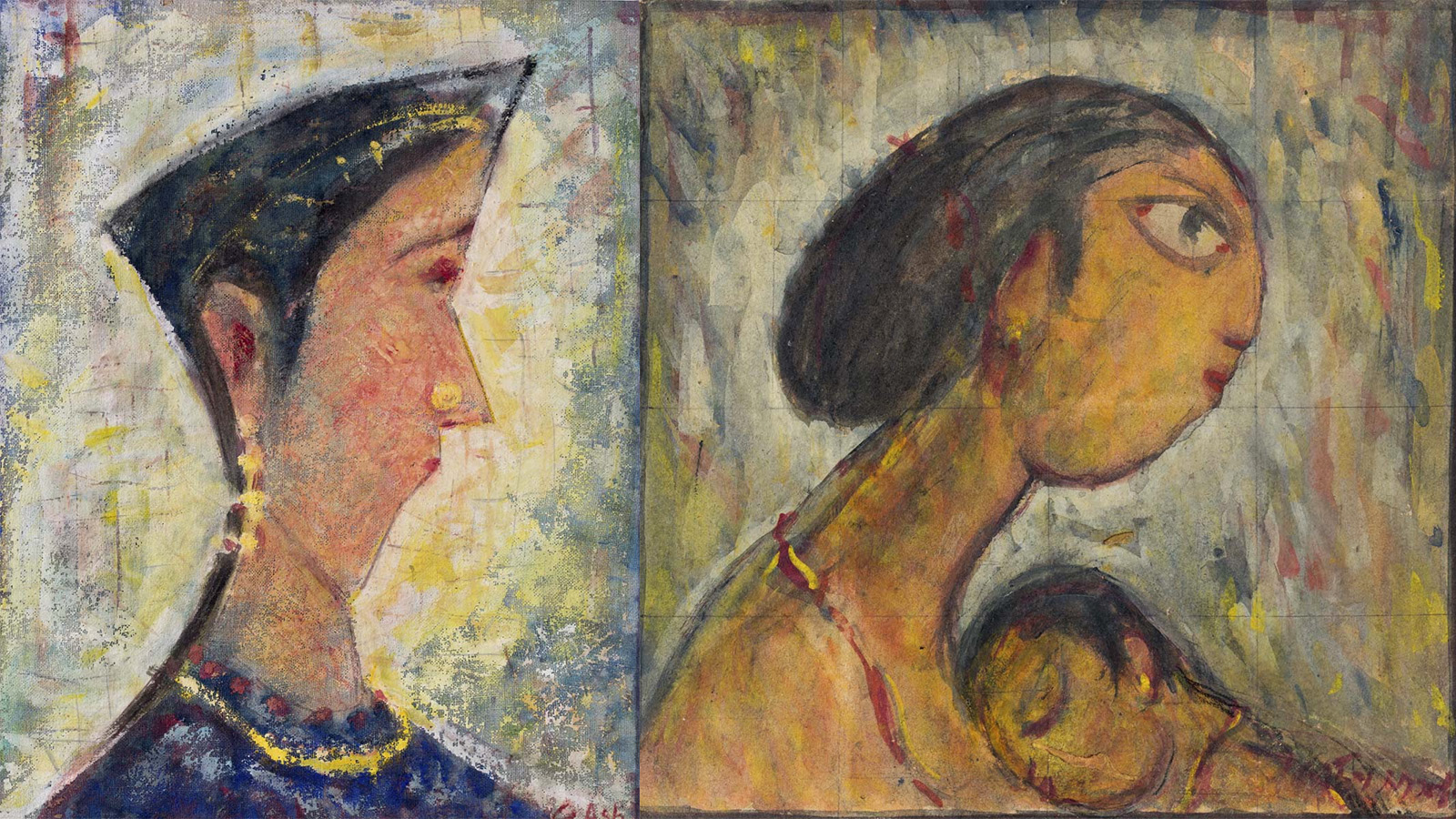

Gobardhan Ash’s “Two Sisters” is one of 35 lots at the auction which were available for purchase as physical works, NFTs, or both. Image: Prinseps

Intriguingly, Prinseps conceived of the Ash NFTs as “avatars,” recognizing parallels between the artist’s unaffected style and the digital collectibles of today. The auctioned portraits, notes Chatterjee, bear “characteristic traits which could be physical, emotional, and cultural traits,” mirroring NFT avatars such as “CryptoPunks [which are] ‘flat’ in execution, characteristic of works on paper.”

It’s a bold association — and appeal to NFT collectors — that belies an admittedly “conservative” auction framework. While Prinseps intended to accept cryptocurrency, “we decided at the end to only accept fiat currency for the NFTs like in any traditional auction,” says Chatterjee. The NFTs, though, are minted on the Ethereum blockchain and transferred to the crypto wallet of the winning bidder. Certainly, the move helps skirt India’s fuzzy legislation surrounding such digital sales, but too, lowers the barrier of entry for traditional collectors.

The NFT for Ash’s 1948 work “Prayer” received the sale’s highest bid of $35,000. Image: Prinseps

And to good effect: all lots at the Ash auction were sold, with the NFTs fetching prices between $12,500 and $35,000. The buyers, as Chatterjee reflects, were “a mixed bag — a combination of traditional bidders and completely new bidders, likely from the crypto world.” The sale has been successful enough that Prinseps has already lined up its second NFT auction, with lots culled from the estate of Bhanu Athaiya, the prolific Indian costume designer who won an Oscar for her work on 1982’s Gandhi.

Prinseps’ faith in India’s burgeoning NFT sphere is not entirely unfounded. As Chatterjee points out, “there are likely more than 100 million crypto wallets in India” — an assertion supported by the latest report from Chainanalysis that revealed a blinding 641 percent growth in India’s crypto market in 2021, just as the country now hosts the world’s second-highest number of cryptocurrency users. “Point being that India has quickly adopted crypto and blockchains,” he continues. “There will be a spillover effect into the NFT market as they are generally closely associated.”

For now, in Chatterjee’s view, India’s commercial sector for NFTs, just like Prinseps’ presence in the space, is only just emerging. “I have a feeling that a few years from now,” he says, “when we look back at this conservatively estimated and priced auction, we will have a bit of a laugh regarding how low the prices were.” But, he adds, “There is always a first step that is required.”