In Tracking the Trends for 2021, Jing Culture & Commerce partners with the cross cultural agency TONG to analyze four key insights for the coming year. Pulling expertise from Jing Group’s network of leading B2B publications, the four-part series covers consumer insights key stakeholders must be aware of to survive post-COVID China. Here, we examine the rise of China’s short-video apps and the future of cultural content consumption.

Key Takeaways:

- Short-video apps, in particular ByteDance’s Douyin, have become dynamic new spaces for consuming art and culture content in China, a trend accelerated in 2020.

- From graffiti artists and iPad illustrators to calligraphy masters and traditional woodworkers, COVID-19 pushed a wave of creators onto Douyin. Creators are shooting step-by-step videos, and talking informally about artist practices to reach new audiences and sell goods. Chinese cultural institutions are following suit with many offering virtual tours and livestreams on Douyin.

- With more than 600 million daily active users, Douyin is close to saturating the Chinese market, and is branding itself as the mainstream’s foremost creative and education platform. In 2019, Douyin platformed 543 billion culture-related plays, and is encouraging this vertical to maintain audiences and increase on-app user time.

- Video length and the connection between short-video and e-commerce are expected to grow in 2021. Douyin has already allowed longer videos as part of a push to deepen content quality and expand usage. ByteDance helped 22 million creators generate $6.9 billion in 2019 and prides itself on being able to offer long-term support for creators.

For the first half of the 20th century, Tianqiao was a microcosm of Beijing’s cultural life. Among its narrow streets and stall-lined squares an informal carnival of fire breathers, crosstalk comics, acrobats, erhu players, and wrestlers offered locals a smorgasbord of human creativity and a taste of the sublime.

Today, however, performances continue across four stages at the Beijing Tianqiao Performing Arts Center, which was erected as part of the area’s redevelopment, but the true spirit of Tianqiao has migrated online to China’s short-video platforms.

Since gaining widespread popularity in 2016, China’s cluster of short-video apps, most prominently, Douyin, Kuaishou, Xigua, and, in some regards, Bilibili, have continually disrupted the country’s internet landscape — and, by extension, how cultural content is consumed. The lip-syncing and synchronized dance routines with which many of the platforms became synonymous are, in fact, only two examples from a diverse cultural ecosystem. Just as visitors to Tianqiao sampled widely, curiously, and haphazardly, so too today’s users swipe between bizarre feats of physical sculpture, calligraphy lessons, tours of contemporary art galleries, and graffiti demonstrations.

High-Culture for the Small Screen (and Mass Audience)

Watching demonstrations of traditional Chinese furniture joinery may not sound riveting, but for woodwork artists Zhang Keke and Zhuang Zhe, short-videos have become the primary means of reaching new audiences and potential customers. EHOOWOOD, their project centered on applying contemporary flair to classical-style Chinese tables, bookcases, and beds, has YouTube videos exceeding a million views and a Bilibili channel with more than 130,000 followers. But in recent months, Douyin has proven the most effective communication tool.

“By watching our videos, the viewers understand the process of making wooden furniture,” says Zhang from EHOOWOOD’s Hangzhou workshop. “From the quality of the materials to the high level of craftsmanship required, we’re not hoping to become internet celebrities here; we’re trying to connect and share, to make our brand last a hundred years.”

Traditional Chinese arts, once the domain of high culture, have begun to transform as young, mass audiences have found new identities in wearing flowing Han dynasty-style garments, playing video games designed with meticulous accuracy to Chinese heritage, and watching hit dramas created in collaboration with prominent museums and cultural sites. Moreover, Douyin is the latest locus of this trend with users discovering new arts content through the platform’s power of recommendation, and ability to group and propel niche content.

As with most everything digital in 2020, the pandemic has accelerated this development and short-video consumption more broadly. New viewing habits begun under lockdown are enduring with a mid-year report from a Chinese internet industry association showing close to 90 percent of China’s internet users regularly use a short-video platform, averaging more than 100 minutes a day.

Ni Zhengpeng is one of countless creators who turned to Douyin to ward off the tedium of lockdown isolation and shared step-by-step art videos. The Central Academy of Fine Arts graduate regularly posts time lapse shorts of his charcoal drawings of barren landscapes and vacant classrooms, scenes that seemed eerily poignant as the city streets around him cleared of people.

“It’s all about the content of the work and figuring out what audiences want,” says Ni whose videos broadened in focus as his fanbase grew to include art book recommendations, reflections on art school, and drawing tips. Pre-pandemic, Ni could not have foreseen turning to short-videos, but feels his content resonates because it shares insights on art and his daily life as an artist.

Cultural Bytes Capture the Mainstream

For Douyin, the presence of arts content as dominant verticals echoes the attentions of the platform’s early millennial adopters. “It started with a core user base of trendy urbanites and art students in the early 20s demographic,” says Matthew Brennan, author of Attention Factory, a book chronicling the rise of parent company ByteDance. “By 2018, Douyin had gone fully mainstream.” Douyin’s warp speed growth was encapsulated by October 2017 during which the app’s users jumped from seven to 14 million and the average time spent in the app doubled to 40 minutes. The growth signaled a reach far beyond the initial Millennial and Gen Z users, and prompted a change of slogan to the all-encompassing “Record Beautiful Life.” Three years on, that vision includes “more than the classic dance, lip-sync, and comic content categories,” says Brennan, and touches upon the full spectrum of cultural content.

Embroidery is one such area. “I had some craft skills before, but I’ve really learned a lot through watching short-videos [on Douyin and Kuaishou],” says Han Yunyin, a retiree in Shanxi province. “Seeing other people’s [embroidery] abilities inspires me to buy more materials and continue making more myself.”

This cultural focus is increasingly driven by ByteDance itself. With more than 600 million daily active users, Douyin appears to have saturated the domestic market — though such predictions in the past have proved premature — and the Beijing-based company’s focus has turned to maintaining its audiences and extending user time, stickiness in industry parlance. Similar to YouTube, Douyin’s appeal rests with content not socializing, says Brennan, and with product teams having seemingly exhausted in-app innovations, the focus will rest on ensuring Douyin platforms unique, quality content. Arts and education are key to this strategy with Douyin self-identifying as China’s largest knowledge, culture, and art platform with nearly 15 million knowledge-based content videos in 2019.

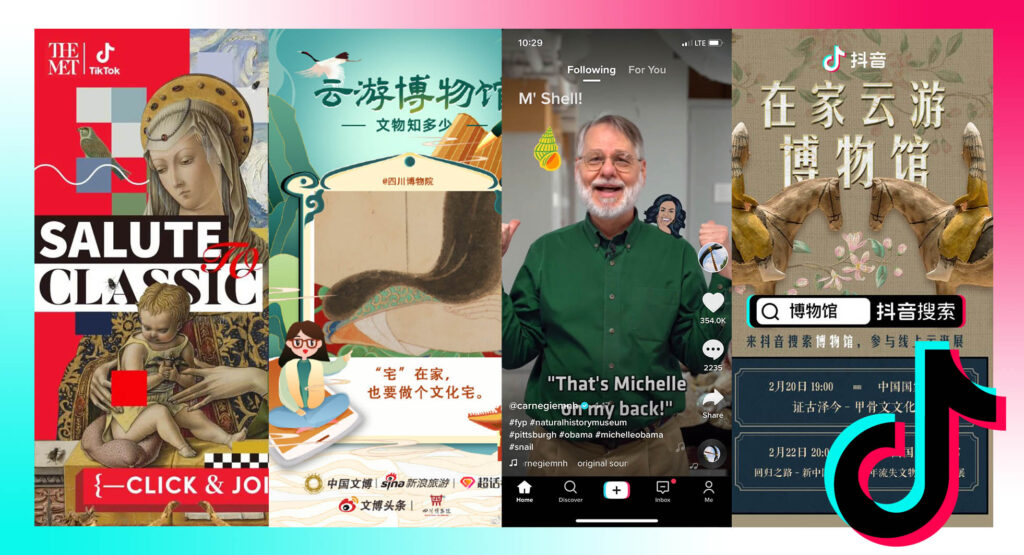

The company claims more than 90 percent of the 1,372 areas of so-called intangible cultural heritages identified by the government have a presence on Douyin. If this seems vague, the arrival of museums on the platform, from giant state institutions such as the National Museum of China to hip contemporary art centers such as Beijing’s UCCA, clearly indicates the new role short-video is playing in delivering culture to large audiences. This move was signified by a 9-museum virtual tour relay held on Douyin in February and a second on International Museum Day in May.

Meanwhile, ByteDance’s desire to elevate arts content is being mirrored internationally with the company launching a $50 million TikTok Creative Learning Fund to support educational content creators and signing with the likes of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, which has enjoyed viral success on TikTok with its series of nerdy science-themed videos.

“The pandemic challenged the whole art industry, but it also offered an opportunity for art institutions and individuals to reflect on how they communicate in this ecosystem,” says Zhu Boer, Activation Manager at TONG, who highlights the range of public and private museums to become active in creating bite-sized informative content. “Launching on short-video platforms seems a must do, but the question in the cultural sector is how to land creatively and contextually.”

Douyin in 2021

ByteDance’s original 15-second video limit led to suggestions of an alternative Andy Warhol vision of a future where everyone would be famous for 15 minutes. But with Douyin creators now able to post five minute-long videos, and go even longer via livestream, the assertion of Warhol’s artistic contemporary Joseph Beuys that “everyone is an artist” more accurately projects the nature of the app in 2021 and beyond.

ByteDance sees supporting individual creators as essential to its long-term success, says Fabian Ouwehand, founder of UPLAB, a Shenzhen-based company that helps artists go viral on Douyin and TikTok. “Douyin uses creators to create an in-app culture and it supports the people on the platform to attract a larger and larger audience.” This support is both practical and financial with 22 million creators receiving $6.9 billion in 2019, a number expected to double in 2020.

Ouwehand has been surprised by the speed at which Douyin has integrated on and offline, thereby allowing calligraphers, potters, and embroiderers to sell their wares through short-videos. ByteDance’s cultural focus, however, is less surprising, “It wants to be seen as the educational and creative platform for the mainstream, to show people good lifestyles and good art. That’s been their messaging since the beginning.”

The continued growth of cultural creators on Douyin will be mirrored by cultural institutions, says Zhang Yilun, a Creative Business Lecturer at the Hogeschool Utrecht, a science university in the Netherlands. “Production-wise, it’s easy to create and operate at a low cost and I expect they will further explore livestreaming shopping options on their existing short-video channels.”

If Douyin is to outlive its own 15 minutes of fame and become the ubiquitous space to consume video on mobile in China, longer, more polished content will be essential, however counterintuitive that might seem. Having succeeded in capturing the attention of China’s internet users at an unprecedented speed, ByteDance will look to support the initiatives of cultural institutions and individual creators in continuing to create the type of culture-centric video that Douyin users have already shown a passion for.