Non-fungible tokens might be promising to prise the art market from the avaricious grip of the one percent, but for the past three years, another digital innovation has been radically transforming the everyman’s ability to collect valuable art — and largely for free.

The culprit is Occupy White Walls, an art-focused sandbox game that encourages players to build galleries defying physics and real estate costs, and then curate exhibitions unbound by artistic provenance. Want a river coursing through a velvet-walled gallery? Not a problem; take your pick from 2,300 architectural assets. Fancy putting Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi” in contentious conversation with his “Mona Lisa”? Why not throw in the game’s 11 other Leonardos, or any of the platform’s more than 17,000 artworks that resonate for that matter?

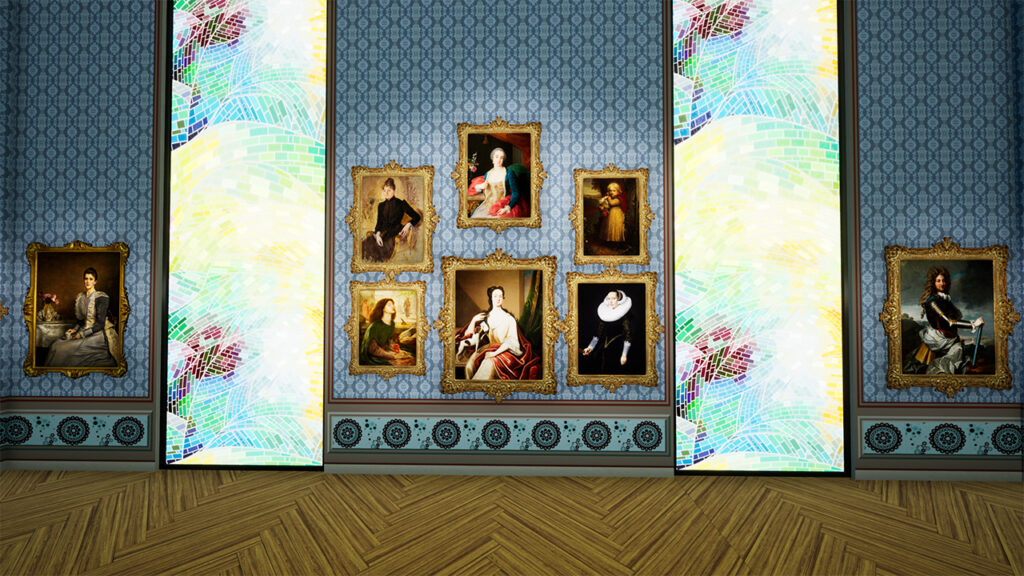

In the spirit of sandbox games like Minecraft, Occupy White Walls lets players build and curate their own virtual museums and gallery spaces, often to imaginative ends. Image: Occupy White Walls

The game is the brainchild of Yarden Yaroshevski, the Chief Executive of StikiPixels, the UK-based tech startup backing the project. Inspired by the broad appeal of Minecraft and the dearth of games promoting “grown-up creativity and civilization” amid a sea of shoot-em-up replicas, Yaroshevski hopes silky smooth world-building and Daisy, the game’s artificial intelligence art recommendation assistant, will help young people rediscover a love of art.

And at a time of widespread cultural lockdown for mainstay museums and niche galleries alike, a wave of hobbyists are indeed turning to Occupy White Walls to discover art and play curatorial oligarch; the game’s players have doubled to around 80,000 over the course of the pandemic.

“Young people are afraid of art; they feel it’s not relevant or only for billionaires. Our vision is to find the art that people will be interested in,” he says, noting Occupy White Walls’ Daisy echoes the way people collect music and receive recommendations on Spotify. The countless “I’m not artsy person, but…” reviews on Steam, the video game distribution platform, support Yaroshevski’s confidence. People might come for the building, but they stay for art and community; as players explore the cornucopia of galleries, they leave comments and chat with fellow curators.

Taking the virtual plunge

BMAG’s virtual representation on the game includes an airy courtyard and skylit galleries. Image: Occupy White Walls

The latest entrant is Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG), the first prominent arts institution to officially partner with Occupy White Walls and design a virtual space on the platform. Unsurprisingly, it’s hardly a like-for-like conversion; visitors can enjoy 19th-century British landscape painting al fresco in a dazzling courtyard, while a Marcel Duchamp Fountain sits in the center of the Grey Room — “because, why not,” jokes Yaroshevski.

The museum is no stranger to ceding digital control having made its collection freely available under the Creative Commons CC0 waiver in 2018. Fittingly, it was through Cut, Copy, Remix, a museum initiative launched to encourage the public to creatively explore its collection of 3,500 publicly available works, that Linda Spurdle, the museum’s Digital Development Manager, became aware of Occupy White Walls.

“We talk a lot about getting younger and more diverse audiences involved,” says Spurdle — a difficult task given the preconceived ideas connected to a museum housed in a grand Victorian building. “Occupy White Walls is a next step. We want people to use our artwork creatively. If people want to build art galleries and exhibitions, go ahead, use our art.”

BMAG’s partnership with Occupy White Walls saw 200 of the institution’s most notable paintings uploaded to the gaming platform for players to curate, display, and engage with. Image: Occupy White Walls

Accessibility is personal for Spurdle. Having grown up in Wrexham, a former mining town in North Wales with no art museum to speak of, it is, by her own admission, “weird” that she discovered a love of art and has since devoted her career to museums. The primacy of digital accessibility that BMAG has been pioneering gained significant traction under lockdown. But despite industry-wide discussions of pivoting and digital reinvention, Spurdle remains skeptical of an inherently conservative sector. “Basically, they’ve tried to do what they were doing before, but online,” she says. “There’s definitely a need to do more.”

For Yaroshevski, the past year’s frenzied talk of museums becoming entertainment juggernauts is misguided. “The job of museums is to look after collections and physical buildings, not compete with global entertainment and media businesses,” he says. “It makes more sense to join a platform and let us do the heavy lifting.”

Uploading 200 of BMAG’s most celebrated paintings such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s “Proserpine” and Frederick Sandys’ “Medea” — “We wanted to have that wow factor,” Spurdle says — was far from onerous, even at a time of furloughed staff and limited resources. The museum plans to add a further 300 works, a process simplified by the digitization and metadata collection undertaken back in 2018.

Beyond the virtues of accessibility, BMAG is now the beneficiary of a constant flow of data on how non-conventional audiences engage with its collection. The information, Yaroshevski claims, is more organic and honest than that gathered on museum websites given player decisions are based primarily on aesthetics. This information might well be used to determine merchandise decisions, Spurdle says, and in the long-term, to launch programming that goes full circle from physical to virtual and then back again.

Overcoming institutional skepticism

As part of its promise to protect an artwork’s integrity and fidelity, Occupy White Walls ensures realistic depictions and metadata security on its platform. Image: Occupy White Walls

Yet, convincing others to follow BMAG’s lead is proving challenging. Occupy White Walls’ commitment to protecting artwork integrity should be persuasive; it guarantees realistic dimensions, prohibits metadata tampering, and prevents artwork stacking. Instead, Yaroshevski notes, museums are more worried by the notion of their works hanging in virtual galleries alongside those of others. Case in point: a player recently unveiled an exhibition featuring all 50 Van Gogh paintings available on the platform.

Such institutional hesitancy speaks to the disruptive power of Occupy White Walls itself, a game that thrusts laymen into the highly-educated realm of art world professionals, allowing them to dismiss traditional practices and the curatorial inconveniences of loans, insurance, and transportation costs with imaginative mouse-clicks. And the legitimacy of provenance concerns? It’s arbitrary, says Spurdle, noting the extent to which museum collections are composed of random legacy donations — late-19th century industrialists in BMAG’s case.

Another holdover of BMAG’s Victorian legacy is its physical building, which is currently closed for an electrical overhaul and set to reopen in 2022. Spurdle was recently asked if the museum might make its lush virtual garden terrace into a physical reality. “It would be nice,” she says, “if only the sun would come out more often.” In Occupy White Walls’ fantasy world, it’s blue skies and sunshine every single day.