Authored by designer and scholar Giorgio Ruggeri, Open History: Designing the Communication of Historical Knowledge Through the Web explores the role of visual design in digital communications about cultural heritage. The book provides insight into how digital platforms and interfaces can be used to tell narratives, and how access to historical sources changes depending on the source.

Showing how the internet has proved instrumental in popularizing and democratizing histories and storytelling, it comes that the digitization of historical sources is directly aligned with a rise in the democratization of historical narrative creation, a practice motivated by a commitment to the sharing of knowledge, characterized by the central role of visual communication design.

Pointing to the “lack of attention on the design of such [history] websites,” Ruggeri examines digital libraries, museums, and archives, the spatial ways knowledge is presented on the Web, and interaction design on historical websites.

Exploring graphic, web, and information design through a series of digital case studies, Open History ultimately suggests that enhanced collaborations between historians and designers are critical in expanding and challenging conventional historical scholarship.

Here are three case studies mentioned in Open History worth a quick look:

An online exhibition with 100 works of net art history whose aim is to sketch a “possible net art canon,” the anthology, in Ruggeri’s words, “challenges the scarcity of historical perspectives on little studied and often inaccessible works.”

The team behind Net Art includes developers, designers, editors, and curators, along with an advisory board of media experts and enthusiasts. Because the focus is on net art, mediation and commentary are mostly absent, with the works displayed directly on the website.

Ruggeri points to the strength of the design of the project, with its “minimalist graphic style and the rough structure of the website,” which borders between “amateurish and modernist.” Later, Ruggeri adds that this visual contextualization is in itself an “aesthetic experience, in which processes of discovery and learning are accompanied by coherent visual systems that valorize the records they display.”

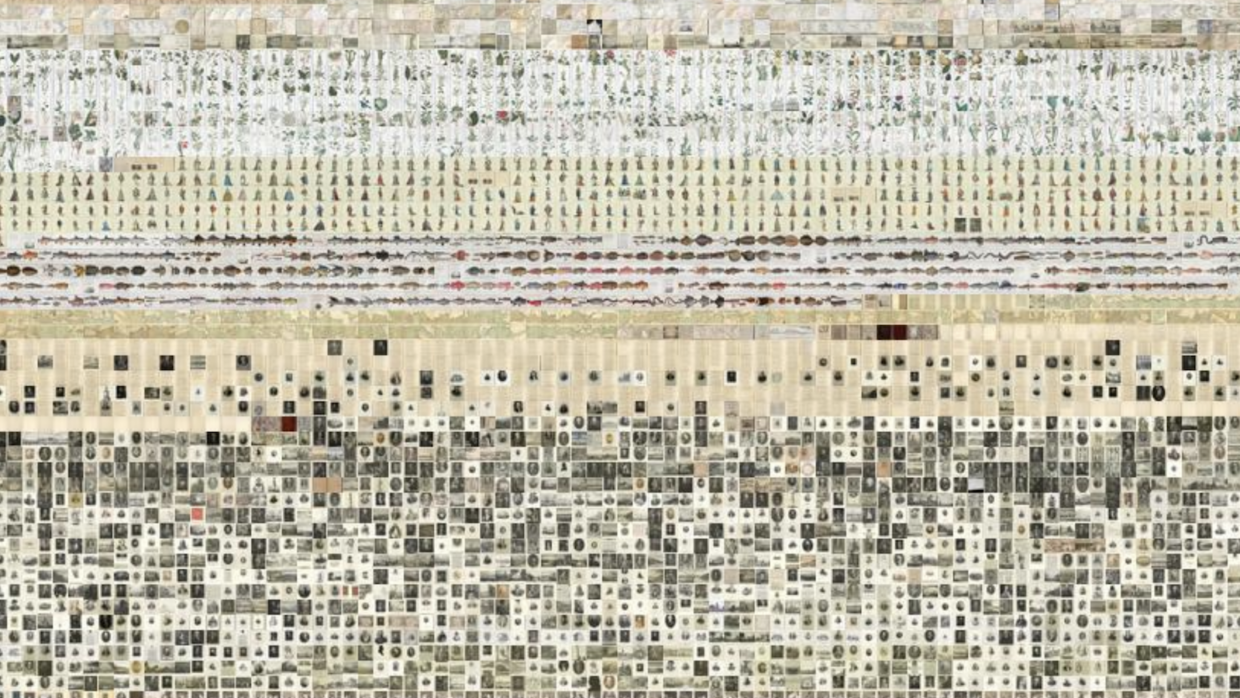

The New York Public Library’s Public Domain Visualization

In 2016, The New York Public Library made over 187,000 digital items in the public domain available for high-resolution download.

Displayed as small thumbnails next to one another, almost as a mosaic, there are four sorting categories for objects: the century in which the items were created, genre, collection, and color.

This is a visualization that emphasizes scope, shock, and collection size over utility. While impressive, the collection doesn’t appear to have been updated since 2016, and its functionality remains limited. One can only sort one category time and one cannot zoom into the thumbnails — they need to be clicked on to be accessed, leaving the main visualization page.

As Ruggeri notes, this makes the project “uncomfortable as an explorative tool,” but it does display the scope and potential of items that have no restricted use.

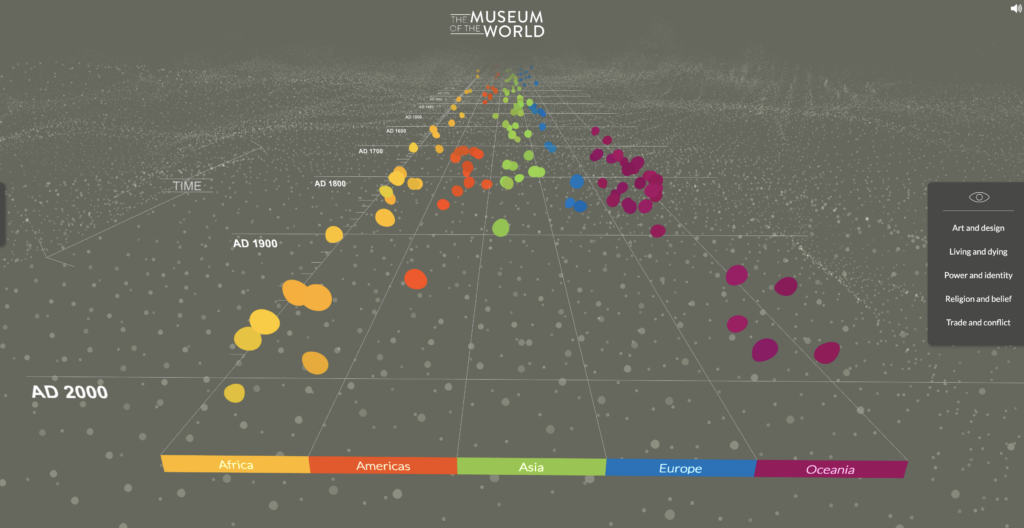

The British Museum and Google Cultural Institute’s Museum of the World:

An interactive timeline with continents, cultures, and objects, this project allows users to discover objects from the British Museum’s collection from prehistory to the present.

“Visitors” learn when and where objects in the collection, represented as dots, come from, which reveals invisible connections between time and space when selected. Five themes — art and design, living and dying, power and Identity, religion and belief, trade and conflict — categorize the artifacts.

Clicking on the dots also reveals popups with detailed information on the artwork, including reproductions, embedded maps showing original provenance, and audio comments containing curator insights. Audio sounds are intermingled throughout the experience, creating a deeper sense of interactivity and engagement, synthesizing the temporal dimension with the digital geography.

Citing this as a successful example of a digital ecosystem because of its enhanced cartographic overlap, Ruggeri cites this project as innovative in how it overcomes the “limited model of temporality inherited by the timeline.”

Three Notable Quotes

- “Communicating history through interactive media is not necessarily an act aimed at the spectacularization of digital technology’s features in favor of impressive, top-down narratives. It can also serve the completely opposite purpose of fostering bottom-up contributions and fragmentary perspectives.”

- “Online access to sources needs to be balanced with web projects capable of popularizing them. This urges approaches to cultural heritage that look at the Web not just as a place for storing materials, but rather as a space for reactivating them.”

- “Digital history still lacks the attention and space needed for a generalized critical awareness… giving visibility to these emerging practices is therefore the first step toward encouraging a debate, in the hope that more designers will be involved in the challenges that history poses in the Information Age.”

Open History is available for purchase here.