Any robust consideration of the contemporary museum experience has to start with four walls and a floor. At its foundation, museological architecture works backwards from emptiness, operating first and foremost as a chamber for the presentation of objects. So what happens to cultural or museum education when our usual interpretations of “space” are no longer viable? In a landscape irrevocably changed by the tandem forces of a global pandemic and digital innovation, museum professionals must reconsider the role, efficacy, and format of educational outreach. So far, teams of coordinators, teachers, and program directors have been tasked with forging new virtual links to the most important audience imaginable: kids.

Prior to COVID-19, museums spent $2 billion on education-based activities every year, three quarters of which were allocated to K-12 programming. Institutions provided more than 18 million hours of targeted education annually, including guided tours, staff visits, school outreach, and professional development for teachers.

Since 2015, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s #MetKids platform has encouraged online discovery through educational videos and interactive features. Image: The Met

These numbers have a profound impact on the cognitive development of future generations: according to the Institute of Museum and Library Services, children who visit museums achieve better grades in reading, math, and science, and even those at risk for deficits due to socioeconomic and/or racial iniquity experience this benefit.

A 2018 study of single-visit field trips to art museums by the National Art Educational Association found that exposure to exhibitions positively influenced kids’ critical thinking skills and imaginative capabilities. Museum collaboration with public schools has been proven to enhance student knowledge of local and state curricula, encompassing a subject base as tailored and diverse as financial literacy, civics, and language arts. Kids benefit from museum education both inside and outside an institution’s doors.

Lockdown-era learning

2020 was not a kind year to museums, and education departments everywhere felt the squeeze. In April of that year, the Museum of Modern Art’s administration caused controversy by terminating all museum educator contracts, effectively expending a population of freelance workers to offset the museum’s temporary closure. It wasn’t alone.

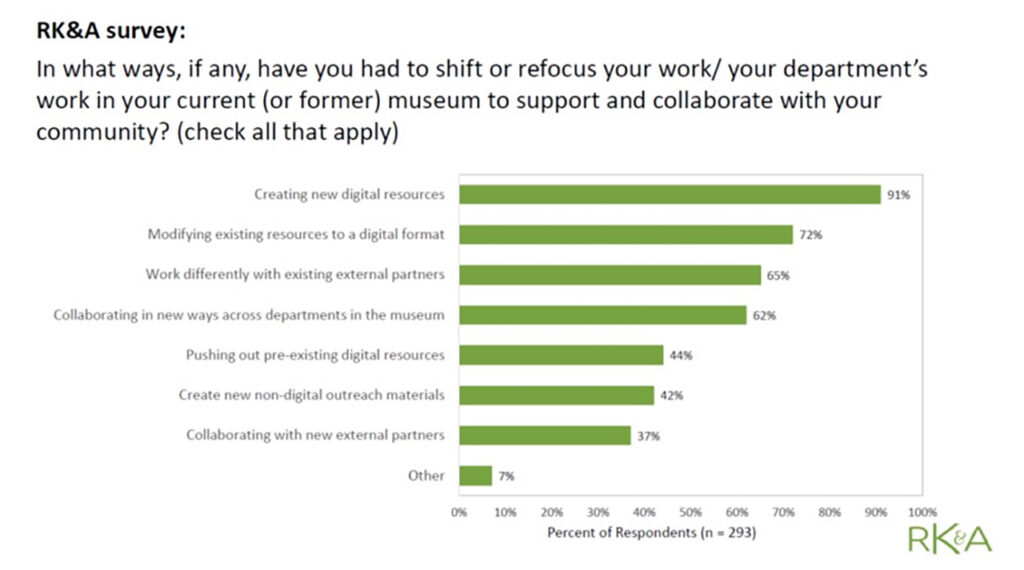

In a January 2021 essay by Juline Chevalier, Director of the Museum Education Division of the National Art Education Association, she reported on a survey conducted by arts and culture evaluation firm RK&A, documenting the impact of COVID-19 on the field. 41 percent of those questioned confirmed that there had been a decrease in full-time or “full-time equivalent” workers in the education departments of their institutions, with contract workers bearing the brunt of those cuts. 91 percent of respondents said that their work shifted to new digital resources, a full third said they were using their own technology to work from home, and another 18 percent reported that virtual programming had to be more or less built from scratch. “The work is still getting done, just with fewer staff and less budget,” noted Chevalier. “We cannot expect things to go back to normal, nor should we want that.”

Typical of lockdown resource allocation, RK&A and National Art Education Association’s survey, which assessed the impact of COVID-19 on the arts sector, saw a huge majority of respondents reporting an acute digital pivot. Image: National Art Education Association

Still, despite infrastructural challenges, museum educators are forging ahead, leaning on a hybrid remote and IRL learning model to bolster results. The Children’s Museum of Houston and Children’s Museum of Manhattan, for instance, have created new daily virtual learning centers, and the New York Hall of Science is bringing its hands-on educational resources online. In the UK, the British Museum has significantly expanded its Virtual Visits program, and University of Cambridge Museums have developed a flagship Arts Pioneers initiative that brings virtual resources to children with disabilities and their families.

J.V. Maranto, Manager of Teen and Family Programs at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City, remarked on some of the unexpected upsides of virtual learning in conversation with Jing Culture & Commerce: “What I love about Zoom and Google Classroom is that folks from all over the world can access our programs and attend our events. In addition, capacity is increased. In person, we might only be able to have 40 visitors participate in a program, but in a virtual setting, we can accommodate hundreds.” She also points out that virtual museum education “allows folks to learn on their own terms” with help from closed captioning and instructions piped directly into their headphones.

Familiarity with this wall-free learning environment has inspired a shift in institutional goal-setting too. “Post pandemic, lots of museums are finally making room in their budgets for sustaining online classes and programming,” says Maranto. “Larger museums already have programs like this especially at the college and post-graduate level — some free, some paid. Smaller institutions have had maybe a family guide or teacher’s guide online, but now are really looking into creating consistent online classes and workshops to retain visitors and keep them engaged. Streaming live programs, creating transcripts of panel conversations, and more social media engagement are also taking the spotlight.”

The matter of accessibility

The New York Hall of Science’s Virtual Science program, which encompasses science showcases and workshops, aims to bring STEM learning to school groups, childcare centers, and other educational organizations. Image: New York Hall of Science

However, there are important drawbacks to consider, especially with at-risk populations who stand to be most directly enriched by museum outreach. “Not everyone has a smartphone, which is really hard for many museums to understand and accept,” Maranto points out. “The same goes for computers — not everyone has a home computer, not everyone has internet, and internet is not always reliable. Remote learning has definitely exposed this.”

Then, there are the logistics of hybridized virtual reality (VR). “Because of the pandemic, giving folks VR equipment or phones to use is a touchy subject because obviously we want to keep our visitors safe and sterilized equipment between uses. Not every museum has the bandwidth to do that,” adds Maranto. Still, she observes that, overall, the pandemic has made museums more accessible. “It’s not perfect, but it’s good to see museums taking the time to look inward and start the work they’ve needed to do all along.”

According to Maranto, it’s also important that post-COVID technology enriches museum education, not the other way around. “Enhancing an exhibition is helpful if it makes sense, but not if it’s done frivolously,” she insists. There’s also ample opportunity in a hybridized future to center different modes of accessible interchange: “Most of the time, museum technology is visually based and that’s not helpful for the 13 percent of Americans (as of 2018) that are visually impaired. Tech can (and should be) something to consider for all senses — smell, touch, taste, feel, hearing.”

Both despite and because of the pandemic’s tragic scourge, cultural institutions have put the futuristic promise of the “open museum” format promised by reformers and academics in the early aughts. Inter-museum and international digital space are now poised to engage visitors who have previously felt unheard and unseen by the pedagogical establishment.