Street Art Museum Amsterdam (SAMA) was founded by Anna Stolyarova in 2012 in the immigrant-heavy Nieuw-West neighborhood in the Dutch capital, which mostly comprised social housing. As someone who worked as a senior digital production director at a large advertising agency, Stolyarova thought that she could use street art to transform the perception about her neighborhood and bring in tourists to boost the local economy.

“Memories” by Colombian street artist Bastardilla, 2019. Image: Street Art Museum Amsterdam

“Safety” by Argentinian street artist Alaniz, 2013. Image: Street Art Museum Amsterdam

As the museum evolved over the last 10 years — building up an enviable collection of around 300 works by some of the world’s most renowned street artists like Pez, Bastardilla, Stinkfish, Btoy, Kenor, and Alaniz — there were many learnings. But none more pressing than the fact that street art is ephemeral. Born with a short life expectancy of three to five years, it fades towards illegibility gradually or disappears suddenly when enforced by the next wave of gentrification. The other realization has been that street artists don’t intend for their works to be restored and would prefer that they be painted over. As a result, only 75 out of the 300 works commissioned by SAMA survive today.

From the early days, the SAMA team started photographing these works as a way to preserve and archive them, mindful of both the fragility and social media appeal of street art. It was also one of the first museums to sign up to Google Culture Institute’s online platform in 2014. However, Stolyarova was aware that digital 2D images did not capture either the monumental appeal of a mural nor the 360-degree experience of the artwork’s environment — and that she needed to explore something more immersive.

An unexpected crisis hastened the adoption. When “Mario,” a much-loved work by French artist Oak Oak based on the video game character, was marked for removal, the local community resisted. Stolyarova opted to use augmented reality (AR) to keep the piece alive. Audiences could now open an app, point their phones towards the wall where the artwork had existed earlier, and “Mario” would pop up.

Another eureka moment came when Stolyarova realized the possibilities of virtual reality (VR) when she attended a presentation by Delft University’s VR department in 2016. But there were still significant roadblocks to execution — from the accessibility of the hardware to the weaknesses in software capabilities. In 2019, a breakthrough came when SAMA was chosen as one of the 17 Impact Hub projects, where, over a series of workshops, start-ups were encouraged to produce a 360-degree VR film from the museum’s collection end-to-end from scripting to shooting and editing.

In the same year, SAMA undertook one of its most innovative VR projects. Centered on Colombian street artist Bastardilla’s monumental project “Memories,” the institution filmed the making of the mural in collaboration with Media College Amsterdam, before the footage was edited into a VR experience. Street artists tend to be very protective about their space while creating a work. Here, VR enabled visitors to access to a unique experience that they are unlikely to ever encounter in real life, making the feedback engaging and memorable.

Above: Screenshot of the simulation of “Memories” by Bastardilla in VR, 2019. Below: SAMA organized special tours and outreach programs for audiences to experience “Memories” using a VR Headset. Images: Street Art Museum Amsterdam

In 2020, when a building housing a parking garage in south east Amsterdam called Garage Kempering was set to be demolished, SAMA worked in collaboration with local institutions to create a VR-based Memory Capsule to preserve the graffiti and the urban environment for the community.

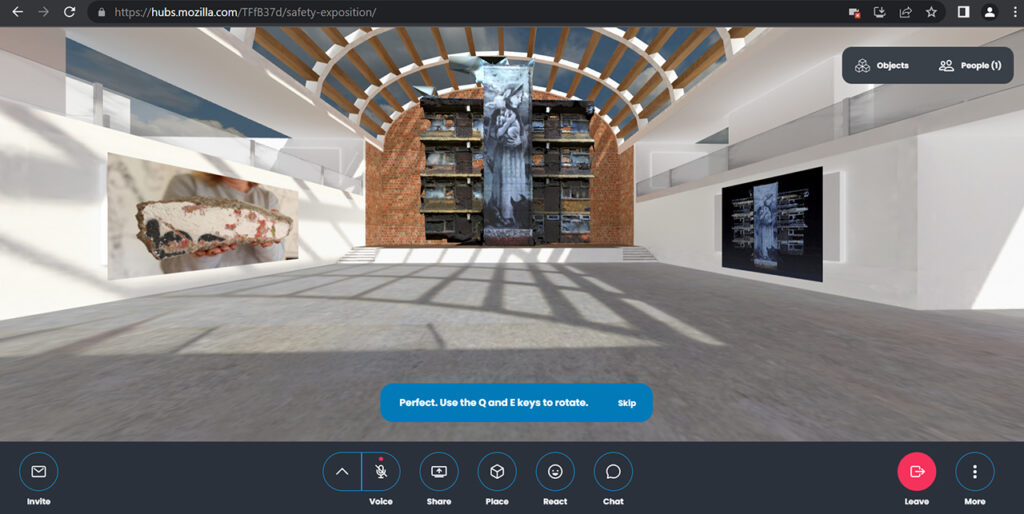

Gabriele Romagnoli, a VR coach and designer who has collaborated with SAMA on immersive exhibition projects, points out that the relative inaccessibility of VR headsets remains a major obstacle, and the intermediate game changer is to enable web-based experiences through a desktop, tablet, or a mobile phone. For one of the works in the collection, “Safety” by Argentinian artist Alaniz, which has been all but lost, he recently used a composite of images from the museum archive and online content to recreate a 3D rendition of the work that then SAMA hosted in an online gallery.

Virtual immersive experience of “Safety,” accessible via desktop or mobile on Mozilla Hubs. Image: Street Art Museum Amsterdam

As a practice, the museum has now instituted 360-degree photography for all its artworks, which will enable bringing them back to life long after the work has physically ceased to exist. Still, fundraising remains a major challenge as authorities often find it difficult to appreciate or classify street art as cultural heritage to be preserved, unlike a work of art a major museum. Currently, the VR projects tend to be artwork-specific, but Stolyarova’s vision for the museum is for its entire collection to be available in an immersive virtual environment in the near future.

Anindya Sen is an independent writer, researcher and cultural strategy consultant who explores themes and issues at the intersections of art and technology, culture and heritage, and emerging artist and market ecosystems. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.