If you have been on the internet over the past year, you will likely have seen the term “NFT,” which stands for “Non-Fungible Token.” NFTs have become extremely pervasive in business and popular culture as of late, but for people outside the wild world of Web3, it may not be so apparent why these funny-looking .jpeg images have amassed such widespread notoriety and adoption.

At a high level, NFTs are essentially a form of verification to show that you actually own something — like a deed to a house. When you buy a house, you gain ownership via a signed, written legal document that we as a society all agree is sufficient and permanent evidence to verify your ownership. The blockchain takes this idea one step further, and allows you to create, or “mint,” a unique identification number (the “token”) that represents a real-world item (usually digital art) onto the blockchain itself. The blockchain functions as a publicly available forum or “ledger,” which shows who owns a particular token at a specific time.

The token displays the identification information of the then-current owner (aka the “wallet ID”), and when that owner sells the token, the next owner’s information shows up on the next “block” in the “chain”. Once minted, the token cannot be changed or altered in any way, nor can it be exchanged for another token, regardless of the value (hence, it is “non-fungible”).

This technology has proven to be very useful to artists for many reasons. For example, NFTs can not only verify the authenticity of a particular work but also carry access to additional benefits (think of it as a VIP ticket to a concert with backstage passes). The other, even more, revolutionary element of NFTs is that via the smart contract (part of the underlying code embedded in the NFT), each time the NFT is sold, a portion of that sale can automatically and instantaneously go back to the original holder, which is normally the artist.

This is important because, prior to NFTs, if an artist (e.g., a painter) sells their work to a gallery for $1,000, then the gallery sells the same artwork for $1,000,000, there is no law, statute, rule or industry practice to ensure that the artist receives any portion of the secondary sale. If the artist’s work is represented by an NFT, however, they can build a mechanism into the smart contract to automatically grant them a portion of that secondary sale, and each subsequent sale, in perpetuity (aka, forever).

Overall, NFTs represent ownership, authenticity, and instant royalty payments. These three things are incredibly important for all types of artists, and especially for musicians and music companies, who have been at the forefront of the development of NFTs and related technology.

Let’s look at the landscape of NFTs specifically as they relate to music.

Historical Context for Music NFTs

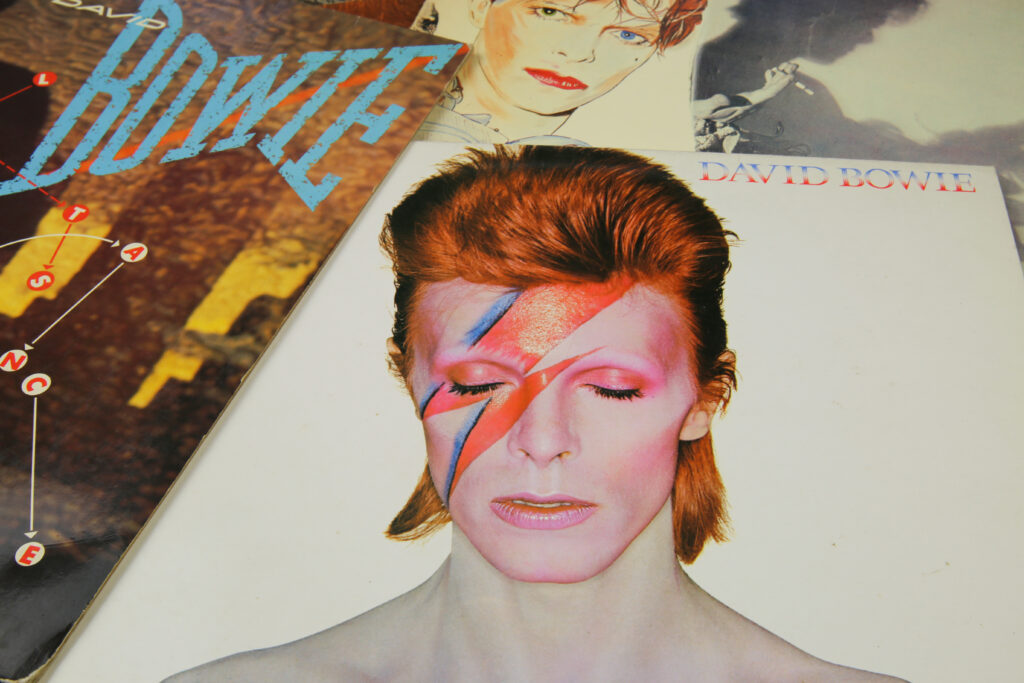

“Bowie Bonds” were launched by David Bowie, his financial manager Bill Zysblat, and banker David Pullman in 1997. Image: Shutterstock

Believe it or not, the first instance of the sentiment of what technology like NFTs could do for musicians first came about when David Bowie created the concept of “Bowie Bonds” in 1997. Purchasers of Bowie Bonds received a security interest to a portion of the revenues derived from Bowie’s catalog of music.

Unluckily for David Bowie, at the time he predicted this concept, the term “digital asset” had not been coined nor was there a blockchain available (though perhaps he traveled to the future in order to gain this knowledge). The biggest limitation for Bowie Bonds was that they were undoubtedly subject to securities regulation, thus limiting the pool of purchasers to those who qualified under the relevant exemption.

To date, we have seen NFTs play out in the music space a little differently than how Ziggy envisioned, but the concept of buying into an artist’s anticipated revenue from their creations has become increasingly more prevalent in this space.

What are the Legal and Business Issues Involved with Music NFTs?

NFT sales come with a variety of legal and business considerations. It is important for people using this technology to always keep in mind intellectual property (“IP”) rights, royalty administration (especially for music NFTs, which is slightly more complicated), and regulatory-related concerns. A few of the important issues we see are:

Intellectual Property

Top Shot users “own” their NFTs, but they are subject to a license from Dapper Labs (via ESPN) that allows the users to do a limited number of things. Image: Shutterstock

In any NFT sale, the purchaser does not receive any IP or other rights to the underlying digital asset without express contractual authorization from the rightsholder. The most common example of this came about when Dapper Labs created the “NBA Topshot” NFTs in 2021. These NFTs contained short video clips of NBA highlights, the rights of which belonged to ESPN. In these very early days of NFTs, there was some confusion as to whether or not selling the NFTs absent the requisite permission violated ESPN’s rights, and what the purchasers could do with those clips.

In short, Top Shot users do “own” the NFT, but the NFT is subject to a license from Dapper Labs (via ESPN) that allows the users to do a limited number of things, such as buying, holding and selling the digital highlight in personal, non-commercial settings. Violating the terms of this NFT agreement could have serious consequences, such as termination of the Top Shot account, rendering the value of the NFT worthless.

Music is no different in this regard. If a musician mints an NFT with the song as the underlying digital asset, then they are not inherently granting ownership of the song to the purchasers. Purchasers of NFTs buy the token itself, and any additional rights to the underlying asset must be granted through a separate contract outlining the specific nature of those rights.

Companies in the NFT space such as the controversial Bored Ape Yacht Club (“BAYC”) have been taking leaps with respect to intellectual property rights, going as far as granting rights to NFT holders that would allow purchasers to freely create their own businesses using the IP in the digital asset of the NFT that they purchased, as well as other broad commercialization rights. However, as innovative as this idea is, this grant of rights is all carefully outlined in the terms and conditions on their website, which functions as the contract subject to which purchasers take the NFTs.

To be continued in Part Two next week.

About the author: With a strong background in music, corporate and general IP law, attorney Danny O’Neill has been working closely with artist and technology clients to find creative solutions to the complex legal issues that arise as a result of working at the intersection of art and Web3, including working with streaming platforms to help navigate the legality of selling music rights as limited digital assets.